Practical Applications of Bsuite For Reinforcement Learning

In 2019, researchers at DeepMind published a suite of reinforcement learning environments called Behavior Suite for Reinforcement Learning, or bsuite. Each environment is designed to directly test a core capability of a general reinforcement learning agent, such as its ability to generalize from past experience or handle delayed rewards. The authors claim that bsuite can be used to benchmark agents and bridge the gap between theoretical and applied reinforcement learning understanding. In this blog post, we extend their work by providing specific examples of how bsuite can address common challenges faced by reinforcement learning practitioners during the development process. Our work offers pragmatic guidance to researchers and highlights future research directions in reproducible reinforcement learning.

0. Introduction

For the past few decades, the field of AI has appeared similar to the Wild West. There have been rapid achievements

This introduction section provides the necessary background and motivation to understand the importance of our contribution. The background section describes how deep learning provides a blueprint for bridging theory to practice, and then discusses traditional reinforcement learning benchmarks. The bsuite summary section provides a high-level overview of the core capabilities tested by bsuite, its motivation, an example environment, and a comparison against traditional benchmark environments. In the motivation section, we present arguments for increasing the wealth and diversity of documented bsuite examples, with references to the paper and reviewer comments. The contribution statement presents the four distinct contributions of our work that help extend the bsuite publication. Finally, the experiment summary section describes our setup and rationale for the experimental illustrations in sections 1-5. The information in this introduction section is primarily distilled from the original bsuite publication

Background

The current state of reinforcement learning (RL) theory notably lags progress in practice, especially in challenging problems. There are examples of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) agents learning to play Go from scratch at the professional level

Fortunately, deep learning (DL) provides a blueprint of the interaction between theoretical and practical improvements. During the ‘neural network winter’, deep learning techniques were disregarded in favor of more theoretically sound convex loss methods

To this end, the trend of RL benchmarks has seen an increase in overall complexity and perhaps the publicity potential. The earliest such benchmarks were simple MDPs that served as basic testbeds with fairly obvious solutions, such as Cartpole

Summary of bsuite

The open-source Behaviour Suite for Reinforcement Learning (bsuite) benchmark

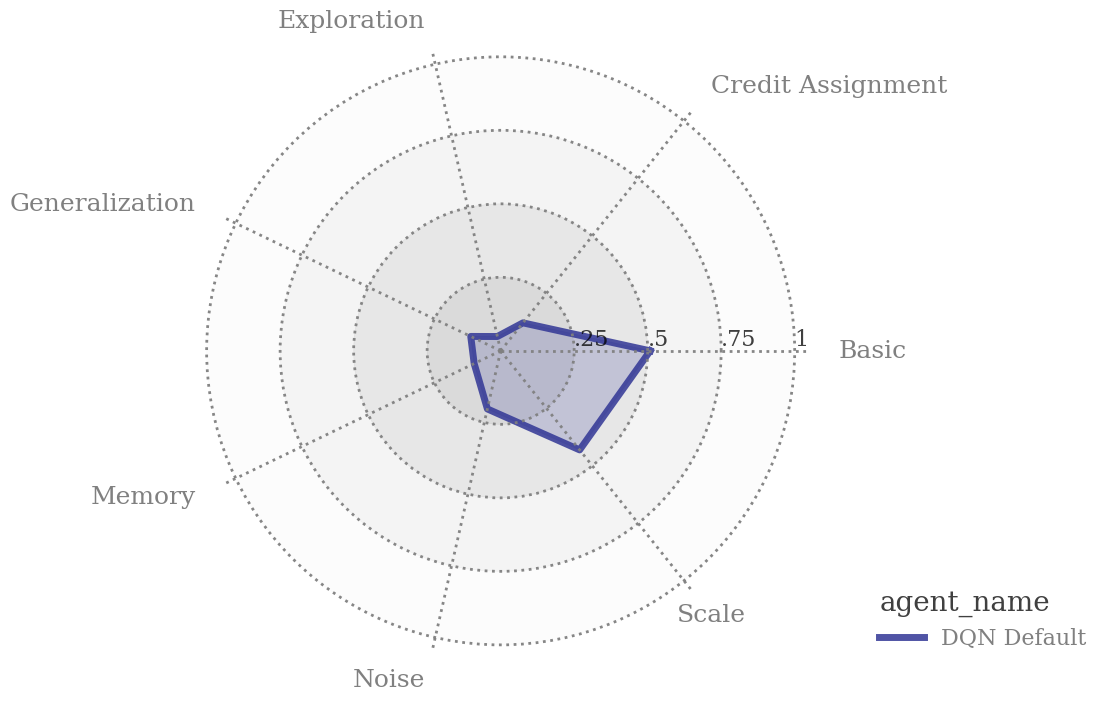

The bsuite evaluation of an agent yields a radar chart (Fig. 1) that displays the agent’s score from 0 to 1 on all seven capabilities, usually based on regret, that yields a quick quantitative comparison between agents. Scores near 0 indicate poor performance, often akin to an agent acting randomly, while scores near 1 indicate mastery of all environment difficulties. A central premise of bsuite is that if an agent achieves high scores on certain environments, then it is much more likely to exhibit the associated core capabilities due to the targeted nature of the environments. Therefore, the agent will more likely perform better on a challenging environment that contains many of the capabilities than one with lower scores on bsuite. This premise is corroborated by recent research that shows how insights on small-scale environments can still hold true on large-scale environments

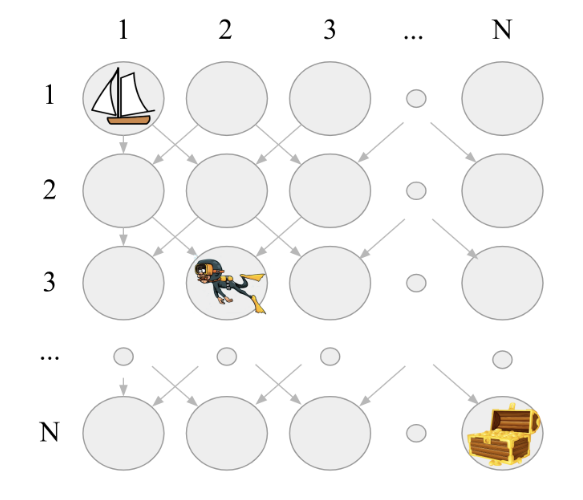

An example environment is deep sea that targets exploration power. As shown in Figure 2, deep sea is an $N \times N$ grid with starting state at cell $(1, 1)$ and treasure at $(N, N)$, with $N$ ranging from 10 to 100. The agent has two actions, move downward left and downward right; the goal is to reach the treasure and receive a reward of $1$ by always moving downward right. A reward of $0$ is given to the agent for moving downward left at a timestep, while a penalizing reward of $-0.01/N$ is given for moving downward right. The evaluation protocol of deep sea only allows for $10K$ episodes of $N-1$ time steps each, which prevents an algorithm with unlimited time from casually exploring the entire state space and stumbling upon the treasure. Note that superhuman performance is nonexistent in deep sea (and more precisely in the entire bsuite gamut) since a human can spot the optimal policy nearly instantaneously. Surprisingly, we will show later that baseline DRL agents fail miserably at this task.

The challenge of deep sea is the necessity of exploration in an environment that presents an irreversible, suboptimal greedy action (moving downward left) at every time step. This environment targets exploration power by ensuring that a successful agent must deliberately choose to explore the state space by neglecting the greedy action. The simplistic implementation removes confounding goals, such as learning to see from pixels while completing other tasks

| Key Quality | Traditional Benchmark Environment | bsuite Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted | Performance on environment subtly related to many or all core capabilities. | Performance on environment directly related with one or few core capabilities. |

| Simple | Exhibits many confounding factors related to performance. | Removes confounding factors related to performance. |

| Challenging | Requires competency in many core capabilities but not necessarily past normal range in any capability. | Pushes agents beyond normal range in one or few core capabilities. |

| Scalable | Discerns agent’s power through comparing against other agents and human performance. | Discerns agent’s competency of core capabilities through increasingly more difficult environments. |

| Fast | Long episodes with computationally-intensive observations. | Relatively small episode and experiment lengths with low observation complexity. |

Motivation

The authors of bsuite stated, “Our aim is that these experiments can help provide a bridge between theory and practice, with benefits to both sides”

The applied examples in the published paper are rather meagre: there are two examples of algorithm comparison on two specific environments and three example comparisons of algorithms, optimizers, and ensemble sizes across the entire bsuite gamut in the appendix. The two examples on the specific environments showcase how bsuite can be used for directed algorithm improvement, but the experiments in the appendices only discuss the general notion of algorithm comparison using bsuite scores. In addition to the examples, the authors supply some comments throughout the paper that provide hints regarding the applied usage of bsuite. Looking at the paper reviews, reviewer #1 mentioned how there was no explicit conclusion from the evaluation, and reviewer #3 mentioned that examples of diagnostic use and concrete examples would help support the paper. Furthermore, reviewer #2 encouraged publication of bsuite at a top venue to see traction within with the RL research community, and the program chairs mentioned how success or failure can rely on community acceptance. Considering that bsuite received a spotlight presentation at ICLR 2020 and has amassed over 100 citations in the relatively small field of RL reproducibility during the past few years, bsuite has all intellectual merit and some community momentum to reach the level of a timeless benchmark in RL research. To elevate bsuite to the status of a timeless reinforcement learning benchmark and to help bridge the theoretical and applied sides of reinforcement learning, we believe that it is necessary to develop and document concrete bsuite examples that help answer difficult and prevailing questions throughout the reinforcement learning development process.

Contribution Statement

This blog post extends the work of bsuite by showcasing 12 example use cases with experimental illustration that directly address specific questions in the reinforcement learning development process to (i) help bridge the gap between theory and practice, (ii) promote community acceptance, (iii) aid applied practitioners, and (iv) highlight potential research directions in reproducible reinforcement learning.

Experiment Summary

We separate our examples into 5 categories of initial model selection, preprocessing choice, hyperparameter tuning, testing and debugging, and model improvement. This blog post follows a similar structure to the paper Deep Reinforcement Learning that Matters

Although running a bsuite environment is orders of magnitude faster than most benchmark environments, the wealth of our examples required us to create a subset of bsuite, which we will refer to as mini-bsuite or msuite in this work. We designed msuite to mirror the general scaling pattern of each bsuite environment and the diversity of core capabilities in bsuite; a complete description of msuite can be found in our GitHub codebase. Running experiments on a subset of bsuite highlights its flexibility, and we will show, still elicits quality insights. Since we use a subset of bsuite for our experiments, our radar charts will look different from those in the original bsuite paper. We generally keep the more challenging environments and consequently produce lower scores, especially in the generalization category.

We stress that the below examples are not meant to amaze the reader or exhibit state-of-the-art research. The main products of this work are the practicality and diversity of ideas in the examples, while the experiments are primarily for basic validation and illustrative purposes. Moreover, these experiments use modest compute power and showcase the effectiveness of bsuite in the low-compute regime. Each example has tangible benefits such as saving development time, shortening compute time, increasing performance, and lessening frustration of the practitioner, among others. To maintain any sense of brevity in this post, we now begin discussion of the examples.

1. Initial Model Selection

The reinforcement learning development cycle typically begins with an environment to solve. A natural question usually follows: “Which underlying RL model should I choose to best tackle this environment, given my resources?”. Resources can range from the hardware (e.g. model size on the GPU), to temporal constraints, to availability of off-the-shelf algorithms

Comparing Baseline Algorithms

Perhaps the first choice in the RL development cycle is choosing the algorithm. A considerable amount of RL research is focused on the corresponding algorithms, which presents many possibilities for the researcher. The No Free Lunch Theorem

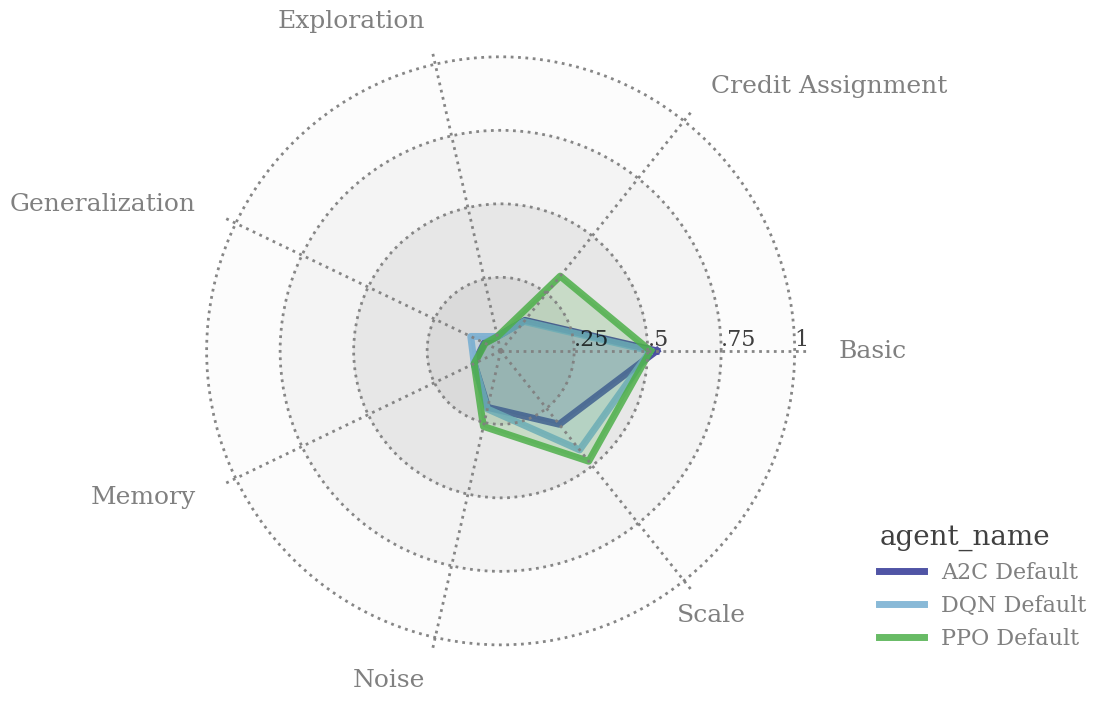

Example: Figure 3 shows the performance of the Stable-Baselines3 (SB3) implementations of DQN, A2C, and PPO on msuite with our default hyperparameters. Recent research

Comparing Off-the-Shelf Implementations

Due to the vast number of reinforcement learning paradigms (e.g. model-based, hierarchical), there are many off-the-shelf (OTS) libraries that provide a select number of thoroughly tested reinforcement learning algorithms. Often, temporal resources or coding capabilities do not allow for practitioners to implement every algorithm by hand. Fortunately, running an algorithm on bsuite can provide a quick glance of an OTS algorithm’s abilities at low cost to the practitioner.

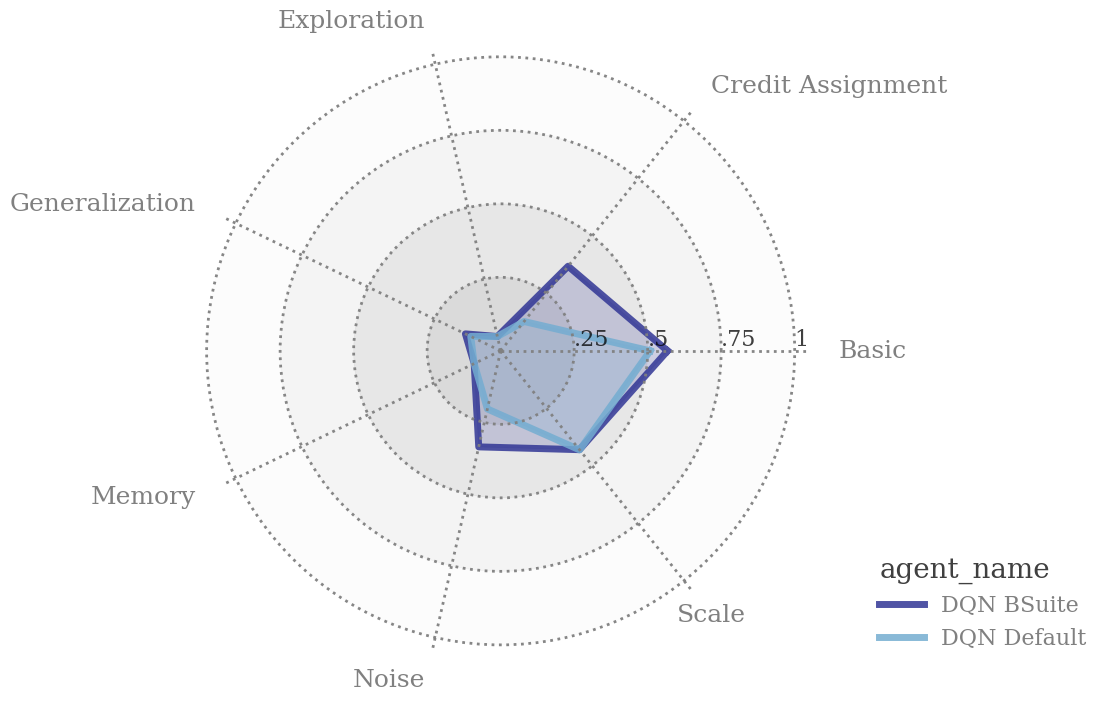

Example: Figure 4 compares our default DQN implementation against the example DQN implementation in the bsuite codebase. There is a significant difference between the performance of each implementation on msuite, with the bsuite implementation displaying its superiority. Note that the hyperparameters of bsuite DQN were most likely chosen with the evaluation on bsuite in mind, which could explain its increased performance.

Gauging Hardware Necessities

Even after an initial algorithm is selected, hardware limitations such as network size and data storage can prevent the agent from being deployed. Using bsuite provides a low-cost comparison among possible hardware choices that can be used to argue for their necessity. This is especially important for small development teams since there can likely be a major disparity between their own hardware resources and those discussed in corresponding research publications.

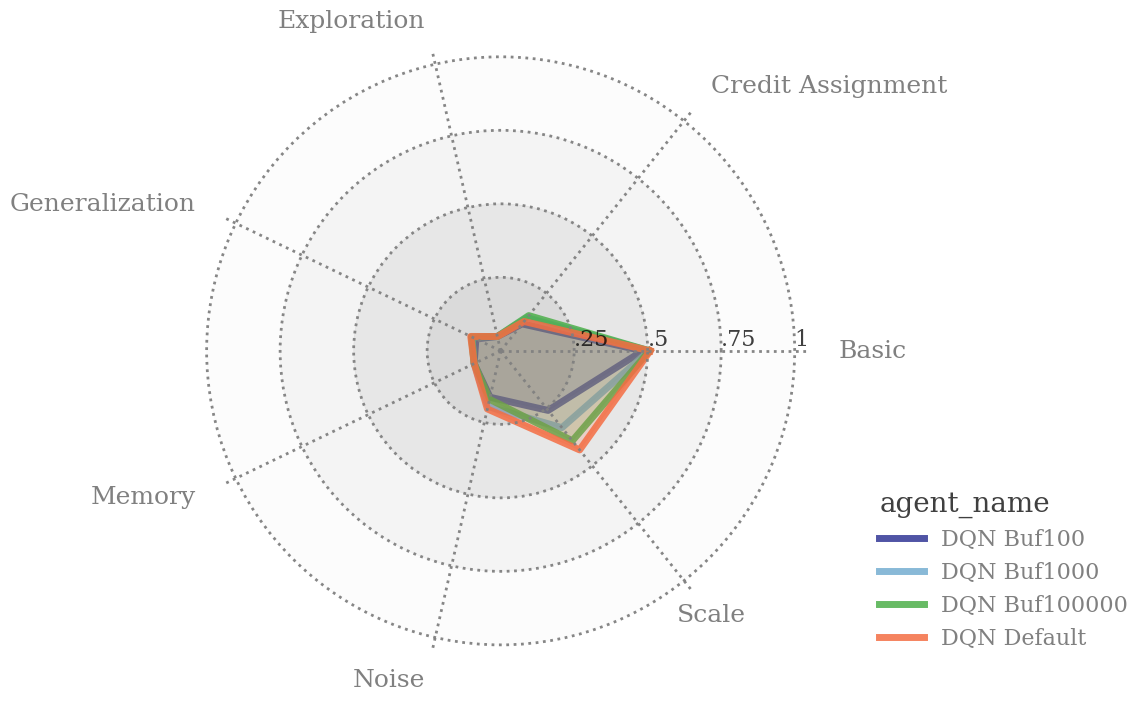

Example: Figure 5 compares the default DQN implementation when varying replay buffer sizes, from $1e2$ to $1e5$, with the default having size $1e4$. The original DQN implementation used a replay buffer of size $1e6$, which is too large for the RAM constraints of many personal computers. The results show that increasing the buffer size to at least $1e4$ yields significant returns on msuite. Note that since the experiment lengths (total time steps for all episodes) of msuite were sometimes less than $1e5$, the larger buffer size of $1e5$ did not always push out experiences from very old episodes, which most likely worsened performance.

Future Work

Due to the diversity of OTS libraries, one possible research direction in reproducible RL is to test algorithms from different OTS libraries using the same hyperparameters on bsuite and create a directory of bsuite radar charts. This provides practitioners a comparison with their own implementation or a starting point when selecting an OTS library and algorithm. Another direction is to test various aspects related to hardware constraints and attempt to show the tradeoff between constraints and performance on bsuite and other benchmarks. This would especially help practitioners with low compute resources to budget resource use on multiple projects.

2. Preprocessing Choice

Most benchmark environments present complexities such as high-dimensional observations, unscaled rewards, unnecessary actions, and partially-observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) dynamics. Some of these difficulties can be curbed using environment preprocessing techniques. While certain environments such as ATARI have formalized standards for preprocessing, there are some aspects such as frame skipping that are considered part of the underlying algorithm, and therefore, a choice of the practitioner

Verification of Preprocessing

Preprocessing techniques usually targeted to ease some aspect of the agent’s training. For example, removing unnecessary actions (e.g. in a joystick action space) prevents the agent from having to learn which actions are useless. While a new preprocessing technique can provide improvements, there is always the chance that it fails to make a substantial improvement, or worse yet, generally decreases performance. Invoking bsuite can help provide verification that the preprocessing provided the planned improvement.

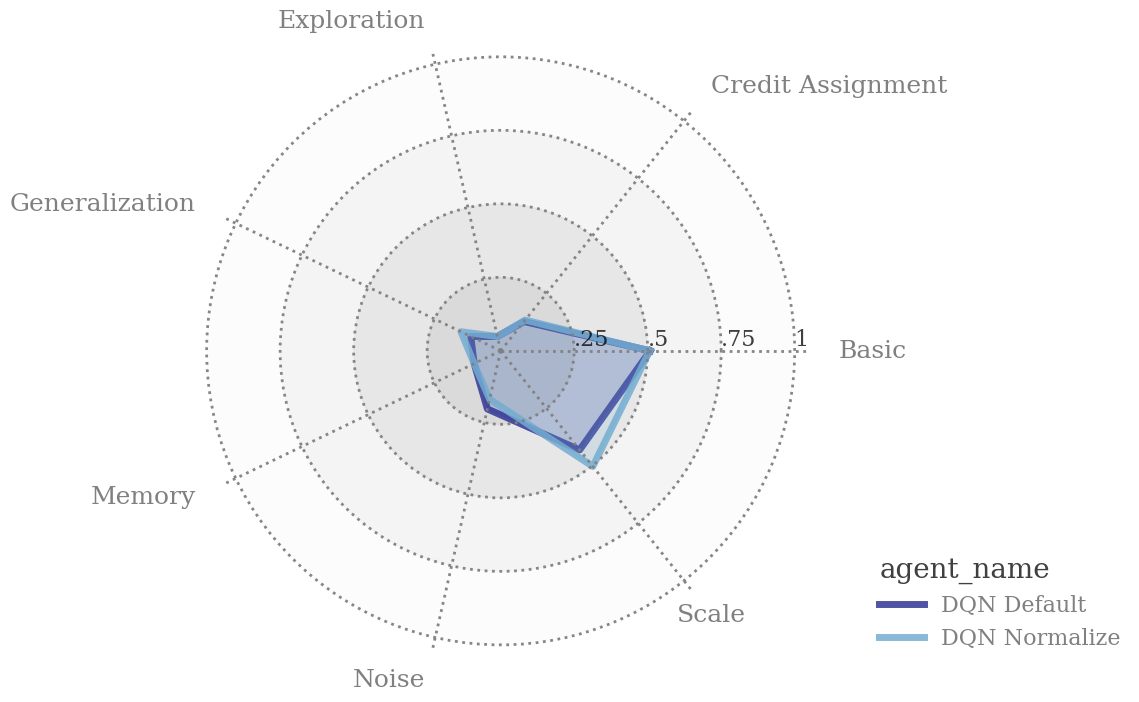

Example: Figure 6 shows the performance of the default DQN agent versus an agent that received normalized rewards from the environment. Normalizing the rewards increases the speed of training a neural network, since the parameters are usually initialized to expect target values in a range from $-1$ to $1$. Our results show that the normalization preprocessing indeed increases the capability of navigating varying reward scales while not suffering drastically in any other capability.

Better Model versus Preprocessing

Instead of choosing to preprocess the environment, a more sophisticated algorithm may better achieve the preprocessing goals. For example, many improvements on the original DQN algorithm have been directed towards accomplishing goals such as improving stability, reducing overestimation, and bolstering exploration. Comparing preprocessing against an algorithmic improvement provides a quantitative reason for deciding between the two options, especially since development time of many common preprocessing wrappers is quite short.

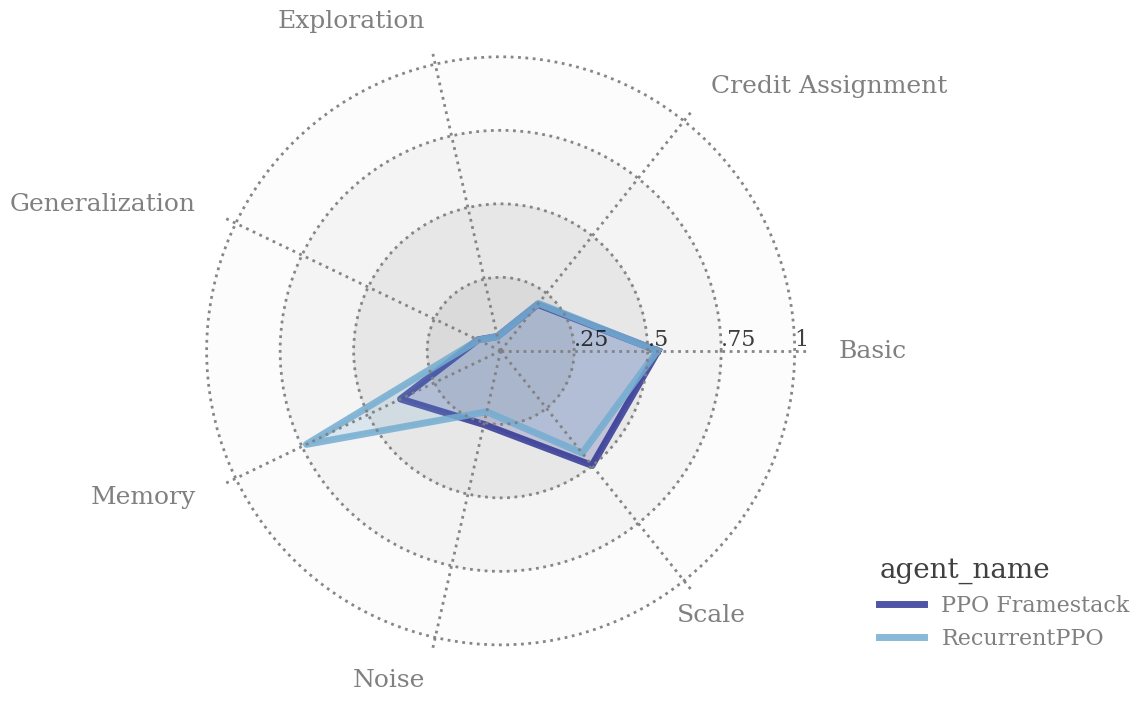

Example: Figure 7 shows the results of PPO with a recurrent network versus PPO having its observation as the last 4 stacked frames from the environment. Frame stacking is common on ATARI since it converts the POMDP dynamics to an MDP, which is necessary to determine velocity of any element on the screen. An improvement to DQN, Deep Recurrent Q-networks

Future Work

One research direction is to document common preprocessing techniques and determine their scores on bsuite. This would provide practitioners a summary of directed strengths for each preprocessing technique while possibly uncovering unexpected behavior. Another direction is to determine the extent to which preprocessing techniques aided previous results in the literature, which could illuminate strengths or weaknesses in the corresponding algorithms.

3. Hyperparameter Tuning

After selecting a model and determining any preprocessing of the environment, an agent must eventually be trained on the environment to gauge its performance. During the training process, initial choices of hyperparameters can heavily influence the agent’s performance

Unintuitive Hyperparameters

Some hyperparameters such as exploration percentage and batch size are more concrete, while others such as discounting factor and learning rate are a little less intuitive. Determining a starting value of an unintuitive hyperparameter can be challenging and require a few trials before honing in on a successful value. Instead of having to run experiments on a costly environment, using bsuite can provide a thoughtful initial guess of the value with minimal compute.

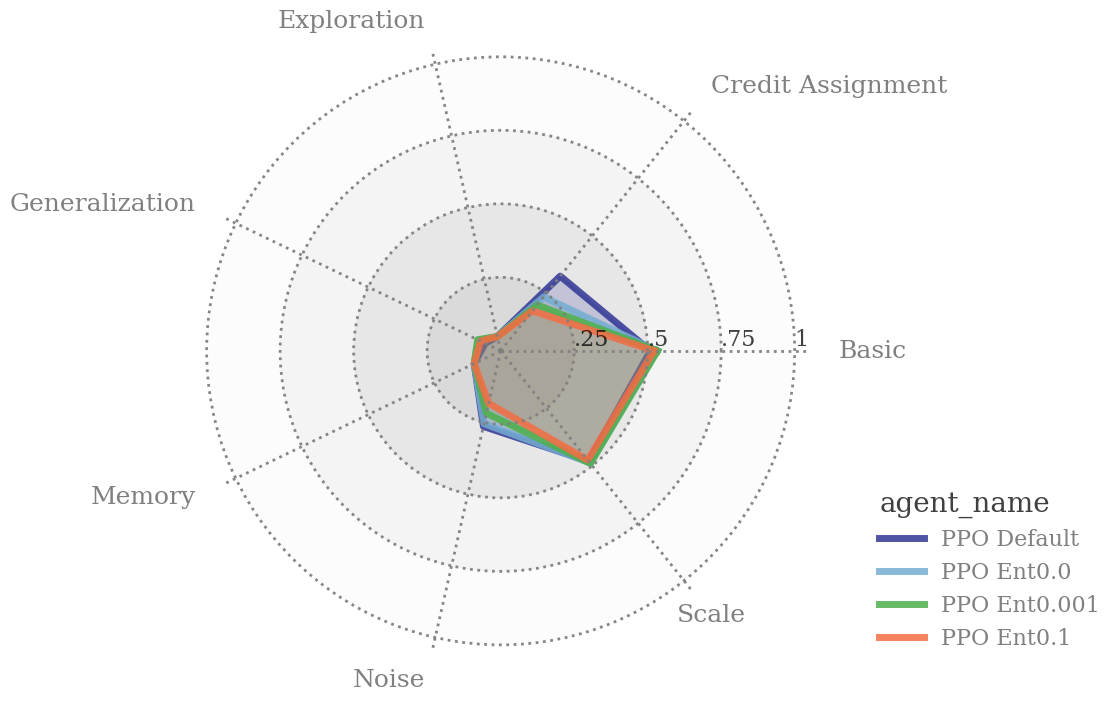

Example: Figure 8 shows the results of running PPO with various entropy bonus coefficients across msuite (default is $0.01$). The entropy bonus affects the action distribution of the agent, and the value of $1\mathrm{e}{-2}$ presented in the original paper

Promising Ranges of Hyperparameters

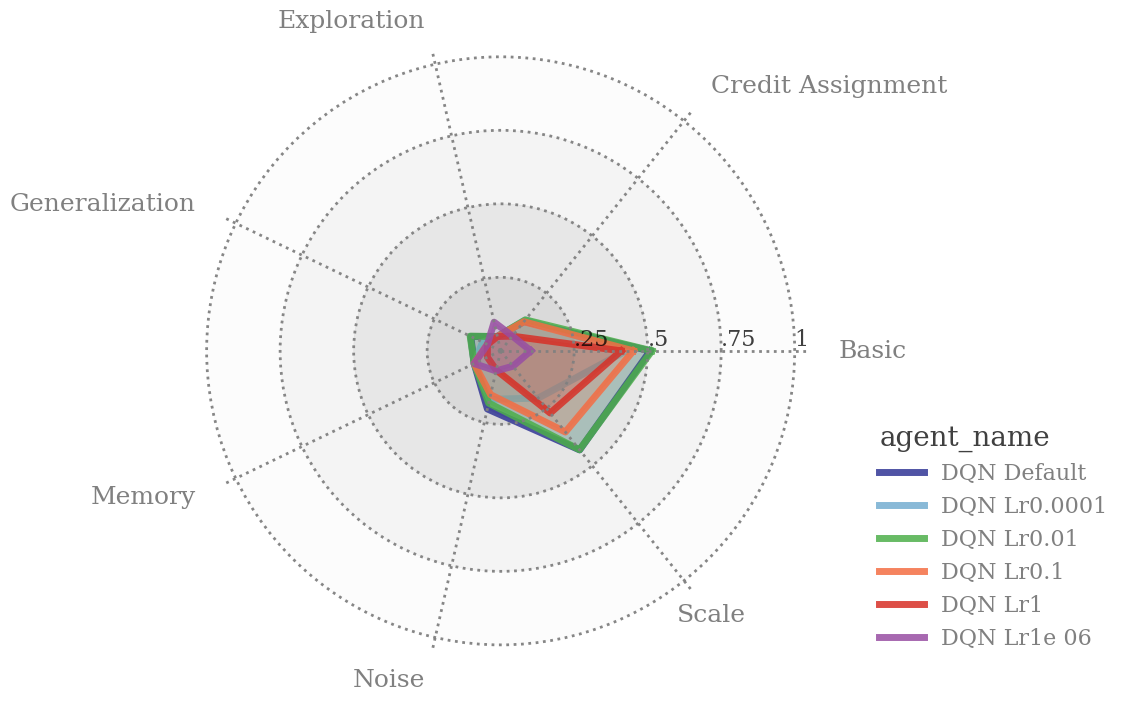

Instead of determining a single value of a hyperparameter, gauging an acceptable range may be required. Since hyperparameters can have confounding effects, knowing approximate soft boundaries of hyperparameters at which agents start to fail basic tasks can provide useful information during a more general hyperparameter tuning process. For example, smaller learning rates generally take longer for algorithm convergence, and a practitioner may want to know a promising range of learning rates if the computing budget is flexible. The scaling nature of bsuite presents knowledge of the extent to which different hyperparameter choices affect performance, greatly aiding in ascertaining a promising hyperparameter range.

Example: Figure 9 shows the results of default DQN with varying learning rates on msuite (default $7\mathrm{e}{-4}$). The results suggest that learning rates above $1\mathrm{e}{-2}$ start to yield diminishing returns. Since some experiment lengths in msuite only run for $10K$ episodes, the lowest learning rate of $1\mathrm{e}{-6}$ may never converge in time even with high-quality training data, necessitating a modification to msuite to learn a lower bound.

Pace of Annealing Hyperparameters

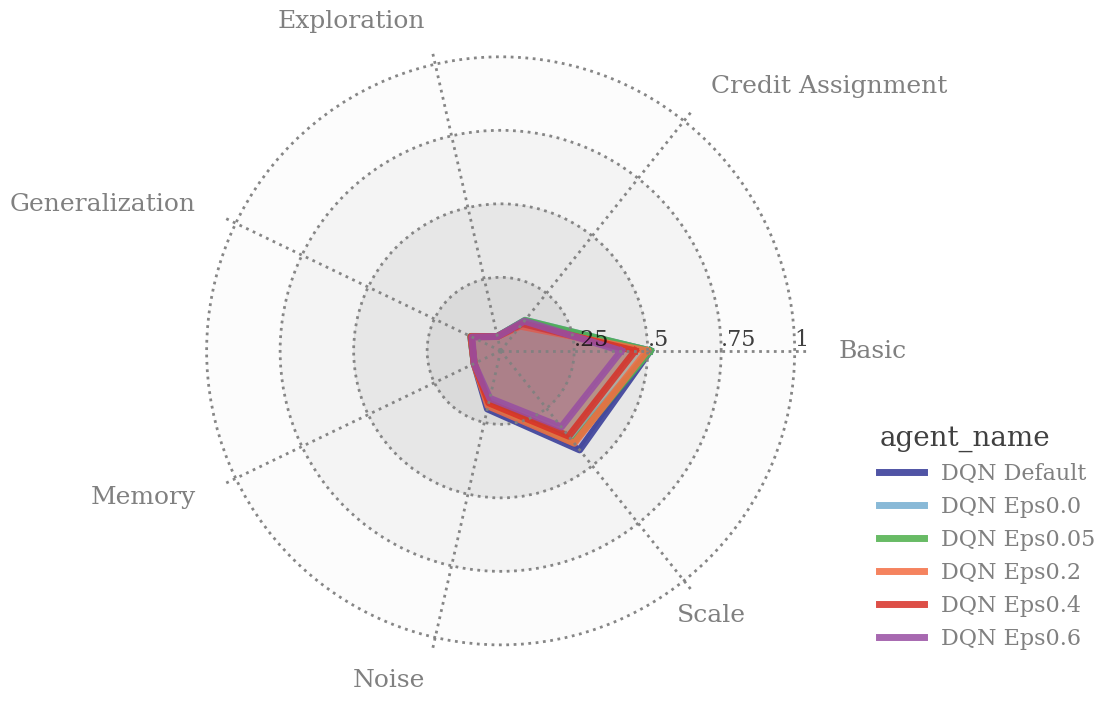

While some hyperparameters stay fixed, others must change throughout the course of training. Typically, these include hyperparameters that control the exploration vs. exploitation dilemma, such as entropy bonus and epsilon-greedy exploration. These hyperparameters are often dependent on the entire experiment; for example, SB3 anneals epsilon-greedy exploration for a fixed fraction of the experiment. Therefore, entire experiments, some consisting of millions of episodes, need to be run to determine successful values of these hyperparameters. Using bsuite can provide a quick confirmation that the annealing of these parameters happens at an acceptable rate.

Example: Figure 10 shows the performance of DQN with various epsilon-greedy exploration annealing lengths, based on a fixed fraction of the entire experiment (default $0.1$). The annealing fraction of $0.1$ performs best on msuite, which is the same choice of parameter in the original DQN paper. Furthermore, performance decreases with greater annealing lengths. Since bsuite environments are generally scored with regret, we acknowledge that the longer annealing lengths may have better relative performance if bsuite were scored with a training versus testing split.

Future Work

The three experiments above can be extended by documenting the effect of varying hyperparameters on performance, especially in OTS implementations. This would help practitioners understand the effects of certain hyperparameters on the bsuite core capabilities, allowing for a better initial hyperparameter choice when certain capabilities are necessary for the environment at hand. Another research direction is to determine if integrating a fast hyperparameter tuner on general environments such as bsuite into a hyperparameter tuner for single, complex environments would increase the speed of tuning on the fixed environment. Since the bsuite core capabilities are necessary in many complex environments, initially determining competency on bsuite would act as a first pass of the tuning algorithm.

4. Testing and Debugging

Known to every RL practitioner, testing and debugging during the development cycle is nearly unavoidable. It is common to encounter silent bugs in RL code, where the program runs but the agent fails to learn because of an implementation error. Examples include incorrect preprocessing, incorrect hyperparameters, or missing algorithm additions. Quick unit tests can be invaluable for the RL practitioner, as shown in successor work to bsuite

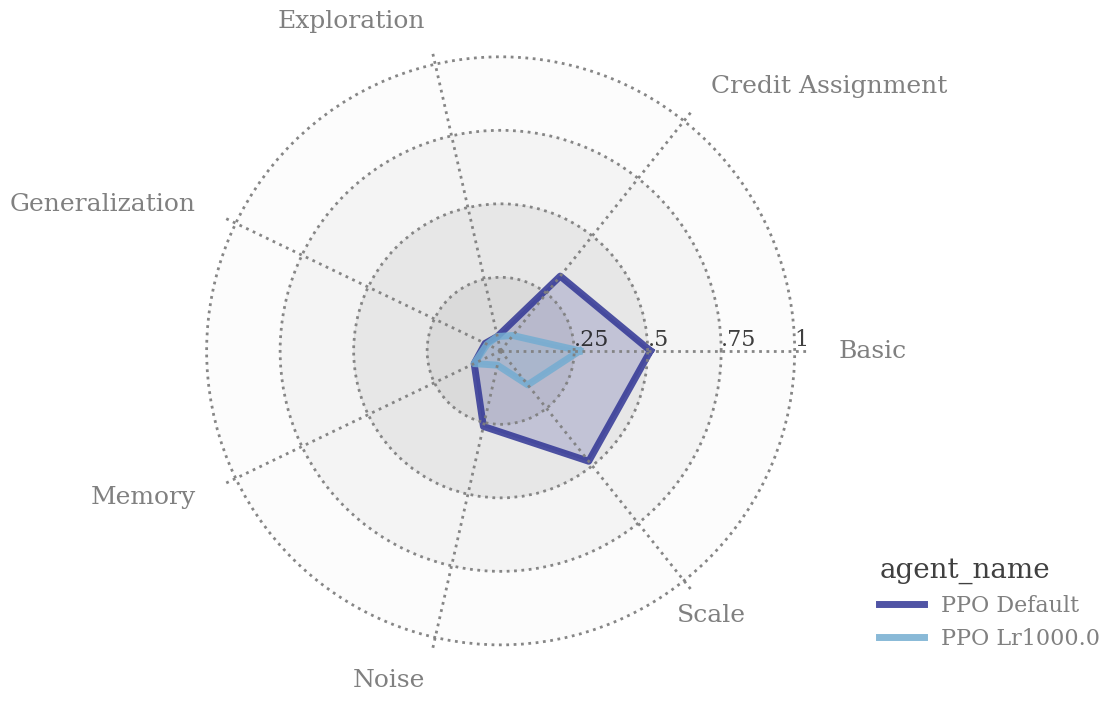

Incorrect Hyperparameter

As discussed in the previous section, hyperparameters are of major importance to the performance of a RL algorithm. A missing or incorrect hyperparameter will not necessarily prevent a program from running, but most such bugs will severely degrade performance. Using bsuite can quickly expose poor performance of an algorithm at a low cost to the practitioner.

Example: Figure 11 shows the default PPO implementation against a PPO implementation with an erroneous learning rate of $1\mathrm{e}{-3}$. Many hyperparameters such as total training steps and maximum buffer size are usually coded using scientific notation since they are so large; consequently, it is easy to forget the ‘minus sign’ when coding the learning rate and instead code the learning rate as $1e3$. The results on msuite show that performance has degraded severely from an OTS implementation, and more investigation into the code is required. One of the authors of this blog post would have saved roughly a day of training a PPO agent in their own work had they realized this exact mistake.

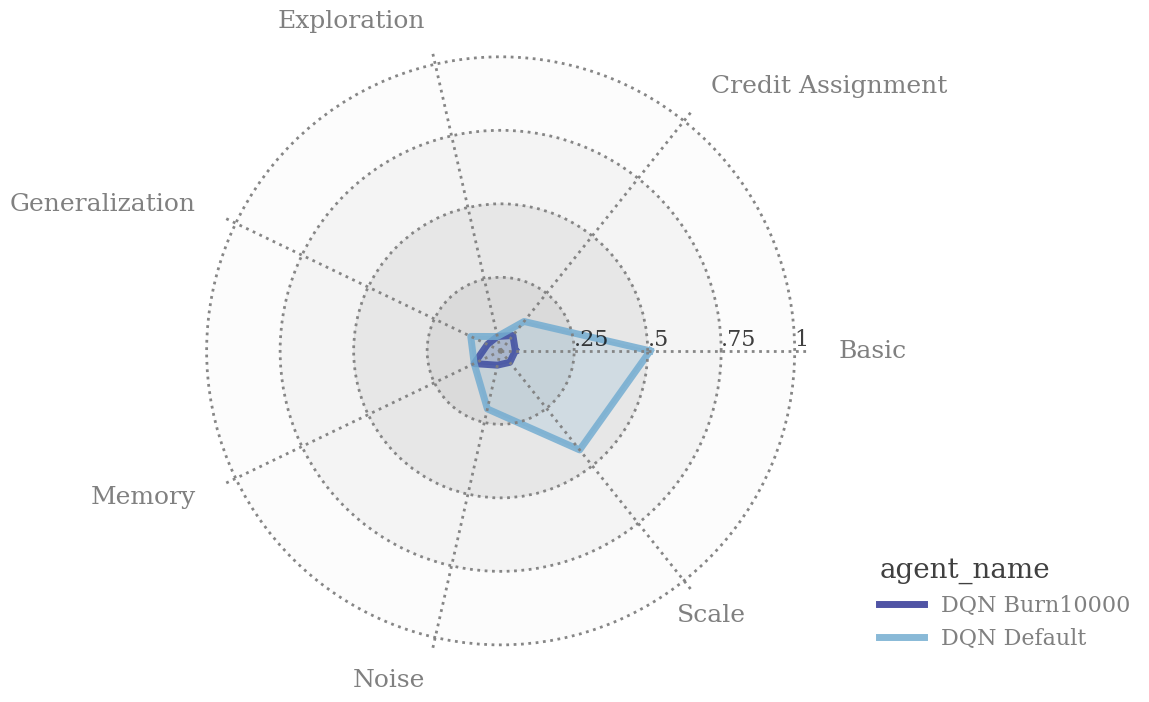

Off-the-Shelf Algorithm Testing

While the previous example used an OTS algorithm for comparison to illuminate silent bugs, it may be the case that the OTS algorithm itself could have a silent bug. Whether due to an incorrect library being used or a misunderstanding of the OTS algorithm, any silent bug in an OTS algorithm can be difficult to detect due to the codebase being written by another practitioner. Again, bsuite can be used to diagnose poor performance and elucidate a coding problem.

Example: Figure 12 shows the results of the SB3 DQN with our default experimental hyperparameters and with the default SB3 hyperparameters on msuite. A core difference between the hyperparameters is the burn rate: the default SB3 hyperparameters perform $10K$ steps before learning takes place (e.g. backprop), while our default experimental hyperparameters start the learning after $1K$ steps. Since many of the easier msuite environments only last $10K$ time steps, failure to learn anything during that time severely degrades performance, as shown. Noticing the default value of this hyperparameter in SB3 would have saved the authors roughly 10 hours of training time.

Future Work

The training time for a complete run of bsuite can take an hour for even the most basic algorithms. Considering that a few of the easiest bsuite environments could have shown poor performance in the above examples within mere minutes, one research avenue is to create a fast debugging system for reinforcement learning algorithms. In the spirit of bsuite, it should implement targeted experiments to provide actionable solutions for eliminating silent bugs. Such work would primarily act as a public good, but it could also help bridge the gap between RL theory and practice if it embodies the targeted nature of bsuite.

5. Model Improvement

A natural milestone in the RL development cycle is getting an algorithm running bug-free with notable signs of learning. A common follow-up question to ask is, “How can I improve my model to yield better performance?”. The practitioner may consider choosing an entirely new model and repeating some of the above steps; a more enticing option is usually to improve the existing model by reusing its core structure and only making minor additions or modifications, an approach taken in the development of the baseline RAINBOW DQN algorithm

Increasing Network Complexity

In DRL, the neural network usually encodes the policy, and its architecture directly affects the agent’s learning capacity. The more complicated CNN architecture was a driver for the first superhuman performance of a DRL algorithm on the ATARI suite due to its ability to distill image data into higher-level features. Using bsuite can provide a quick verification if an architectural improvement produces its intended effect.

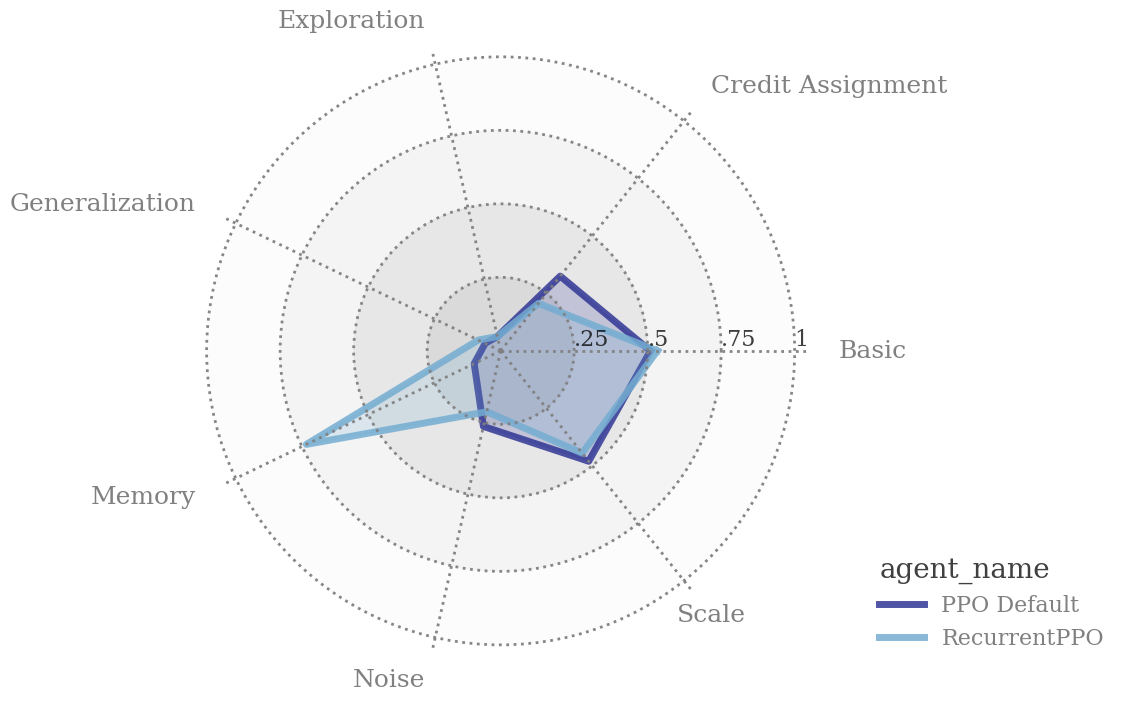

Example: Figure 13 shows the results of PPO against PPO with a recurrent neural network. As mentioned in a previous example, RNNs aid memory and were originally incorporated into DRL as a way to deal with POMDP dynamics. The results on msuite display the substantial increase in memory capability while sacrificing on credit assignment. This example highlights how bsuite can provide warnings of possible unexpected decreases in certain capabilities, which must be monitored closely by the practitioner.

Off-the-Shelf Improvements

While previous examples discussed comparison, verification, and debugging OTS implementations, many OTS libraries provide support for well-known algorithm improvements. For example, some DQN implementations have boolean values to signify the use of noisy networks, double Q-learning, and more. Using bsuite provides the necessary targeted analysis to help determine if certain improvements are fruitful for the environment at hand.

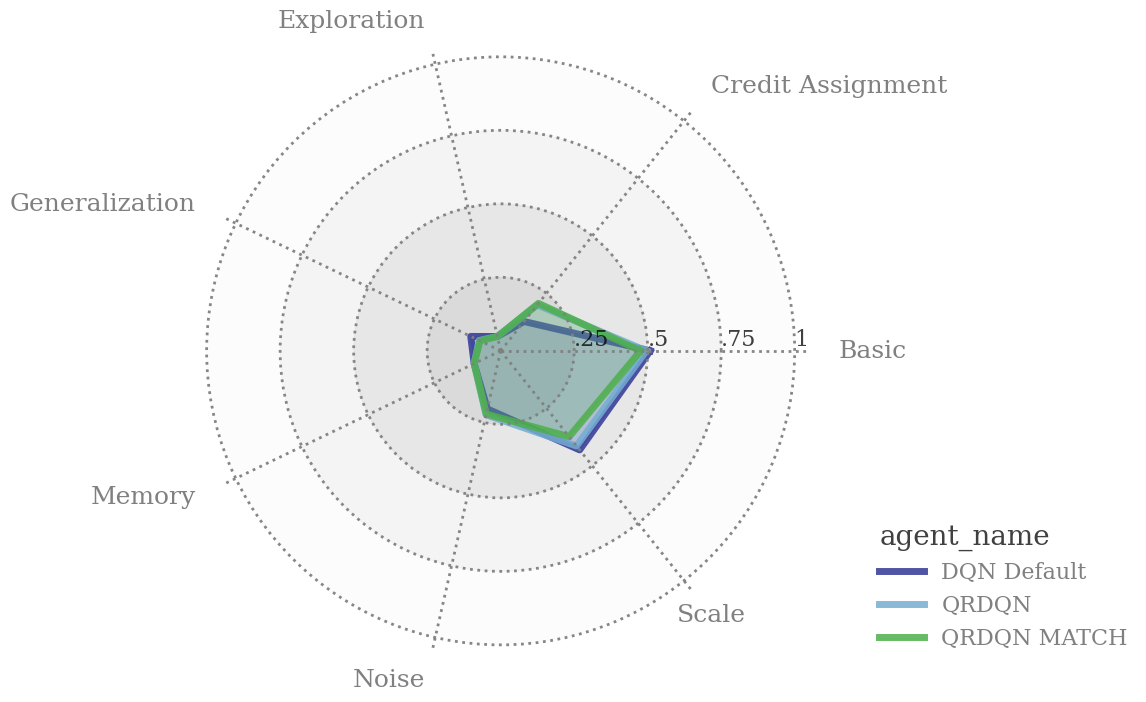

Example: Figure 14 shows the results of our default DQN compared against the SB3 QRDQN algorithm with default hyperparameters and the SBE QRDQN algorithm with hyperparameters matching our default DQN implementation. The QRDQN algorithm is an improvement over DQN that aims to capture the distribution over returns instead of a point estimate of the expected return. This implementation is more complex but allows for a precise estimate that aids in stability. The results show that this improvement was rather negligible on msuite, and unless credit assignment is the major concern in the environment at hand, a different improvement may prove more useful.

Future Work

Since bsuite provides quantitative results, one avenue of research is to create a recommender system that uses information from previous bsuite analyses to recommend improvements in DRL algorithms. The practitioner would need to provide as input the most important capabilities that an environment is believed to exhibit, and bsuite would tailor recommendations towards those capabilities. Such a recommender system could save compute time, increase performance, and ultimately expose the practitioner to new and exciting algorithmic possibilities.

6. Conclusion

Traditional RL benchmarks contain many confounding variables, which makes analysis of agent performance rather opaque. In contrast, bsuite provides targeted environments that help gauge agent prowess in one or few core capabilities. The goal of bsuite is to help bridge the gap between practical theory and practical algorithms, yet there currently is no database or list of example use cases for the practitioner. Our work extends bsuite by providing concrete examples of its use, with a few examples in each of five categories. We supply at least one possible avenue of related future work or research in reproducible RL for each category. In its current state, bsuite is poised to be a standard RL benchmark for years to come due to its acceptance in a top-tier venue, well-structured codebase, multiple tutorials, and over 100 citations in the past few years in a relatively small field. We aim to help propel bsuite, and more generally methodical and reproducible RL research, into the mainstream through our explicit use cases and examples. With a diverse set of examples to choose from, we intend for applied RL practitioners to understand more use cases of bsuite, apply and document the use of bsuite in their experiments, and ultimately help bridge the gap between practical theory and practical algorithms.

Green Computing Statement

The use of bsuite can provide directed improvements in algorithms, from high-level model selection and improvement to lower-level debugging, testing, and hyperparameter tuning. Due to the current climate crisis, we feel that thoroughly-tested and accessible ideas that can reduce computational cost should be promoted to a wide audience of researchers.

Inclusive Computing Statement

Many of the ideas in bsuite and this blog post are most helpful in regimes with low compute resources because of the targeted nature of these works. Due to the increasing gap between compute power of various research teams, we feel that thoroughly-tested and accessible ideas that can benefit teams with meagre compute power should be promoted to a wide audience of researchers.

Acknowledgements

{Redacted for peer-review}