Language and (Meta-) RL - An ode to structure

It has been argued that language can be a very powerful way to compress information about the world. In fact, the learning of humans is significantly sped up around the time they start understanding and using language. A natural question, then, is whether the same can be argued for sequential decision-making systems that either learn to optimize a single or multiple, task. To this end, there has been a surge of works exploring the use of Language in Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Meta-RL. The goal of this blog post is to try and explain some of the recent works in this sub-field and help elucidate how language can help with incorporating structure about the environment to improve learning generalization in (Meta) RL

Introduction

When Wittgenstein wrote, “Die Grenzen meiner Sprache bedeuten die Grenzen meiner Welt” (The limits of my language constitute the limits of my world), I doubt he would have even remotely imagined a world where one could ask a large language model like ChatGPT ‘Can you provide me Intelligent quotes on language by famous philosophers?’ before writing one’s blog on the role of language for Reinforcement Learning.

Yet, here we are, living in a time where sequential decision-making techniques like Reinforcement Learning are making increasingly larger strides, not just in robot manipulation

Parallelly, another Cambrian explosion has been happening in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP). Language models have come a long way since the days of word embedding and sequence-sequence models, to the agent of attention and pre-trained models. Crucially, as this growth continues with newer innovations like ChatGPT, it also leads us to innovative applications of these language models in other fields of Machine Learning, including Reinforcement Learning

In this blog post, I will explore the connection between Natural Language and RL through some recent and not-so-recent ICLR publications that I find very interesting. Since this topic is vast, so much so that a full survey has been written on it (

RL basics

To better cater to audiences beyond the RL community, I think it would be good to briefly revise some core concepts. RL folks are more than welcome to skip to the next section. I am going to try my best to keep it less math-oriented, but I apologize in advance on behalf of the symbols I will use.

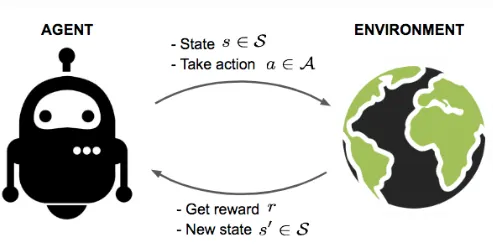

(Picture Credits: https://jannik-zuern.medium.com/reinforcement-learning-to-survive-in-a-hostile-environment-3658624a5d83)

The key idea in RL (shown in the figure below) is to model the learning process as an agent acting in an environment. At every time-step $t$, the environment exists in a state $s$ and the agent can take an action $a$ to change this state to $s’$. Based on this transition, the agent gets a reward $r$. This process is repeated either for some number of steps until a termination condition is reached (also called episodic RL), or indefinitely (Non-episodic RL).

A common way to specify such problems is using Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), which can be written as a Tuple $\mathcal{M} = \langle \mathcal{S}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{P}. R, \rho \rangle$ where

- $\mathcal{S}$ is the state-space i.e. states are sampled from this space

- $\mathcal{A}$ is the action space

- $P: \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \to \Delta(\mathcal{S})$ is a kernel that defines the probability distribution over the next states i.e. given a state and action, it tells us the probability of ending in the next state

- $R: \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \to \mathbb{R}$ is the reward function

- $\rho$ is the initial state distribution

The aim of the agent is to maximize the sum of rewards obtained, a quantity called the return $G_t$, by learning a policy $\pi$ that either maps a given state to an action (deterministic policies), or distributions over actions (stochastic policies). Thus, we can model any task $\tau$ using the MDP formalism and train an RL agent to learn to policy to solve this task.

Language, Generalization, and Multi-Task RL

When we talk about settings that go beyond solving a single task $\tau$ we are faced with the problem of training an agent to solve multiple MDPs $\mathcal{M}_1, \mathcal{M}_2, \dots$, and this is non-trivial. While we want the agent to learn to perform well at these tasks, we don’t want to do it the naive way by training the agent to perform all of these tasks separately. Thus, the key challenge is to figure out a way to make this problem more tractable.

A good point to try to look for solutions is to take inspiration from how humans learn in the real world. This is where the idea of knowledge reuse comes into the picture. Consider the case of learning how to ride a motorcycle. This can be broken down into a sequence of tasks like learning how to balance yourself on a motorcycle, learning how to navigate a two-wheeler, learning how to run a motor-based vehicle, etc. A lot of these skills can be acquired even before we come near a motorcycle through other tasks. For example, learning how to walk teaches us navigation, while learning how to ride a bicycle teaches us things about two-wheelers, and so on. Thus, when a human would come to the task of learning how to ride a motorcycle, they would essentially reuse a lot of skills that they have learned before. In other words, humans meta-learn between tasks.

If we look a bit deeper into this process, some interesting concepts come to the forefront:

- The only reason a human can meta-learn between these tasks incrementally is that there is an overlap between the requirements of solving these individual tasks. In other words, there is some underlying structure that can be captured by a learner between tasks that allows them to transfer learned knowledge between tasks

- Given a learned set of skills, any problem that can be solved by composing these skills can be potentially solved by a learner who has acquired these skills. IN other words, complex tasks that have an underlying compositional structure can be solved by learning individual components and combining them

So, when we translate this to the problem of solving a collection of MDPs $\mathcal{M}_1, \mathcal{M}_2, \dots$, one of the key bottlenecks is figuring out a way to capture the underlying structure between them. Naively, we could implicitly learn this structure, and a lot of techniques in Meta-RL do exactly this. But what if we had some additional side information that we could leverage to do this more easily?

This is where language shows its importance. The world is full of structure in the form of relations between objects (Relational Structure), Causal relationships between events (Causal Structure), etc. Crucially, while humans do meta-learn between individual tasks, this ability is significantly bolstered and catalyzed by the existence of language

Idea 1 - Policy Sketches

Source:

When we talk about composing skills, a long line of work in RL has been on the idea of learning policies hierarchically (Hierarchical RL). For example, in the task of locomotion, controllers can learn individual control policies while a higher-level controller can learn a policy whose actions are to coordinate the lower-level controllers. This is similar to how we try to solve a problem using the dynamic programming method — by breaking it down into subproblems and then combining the solutions together.

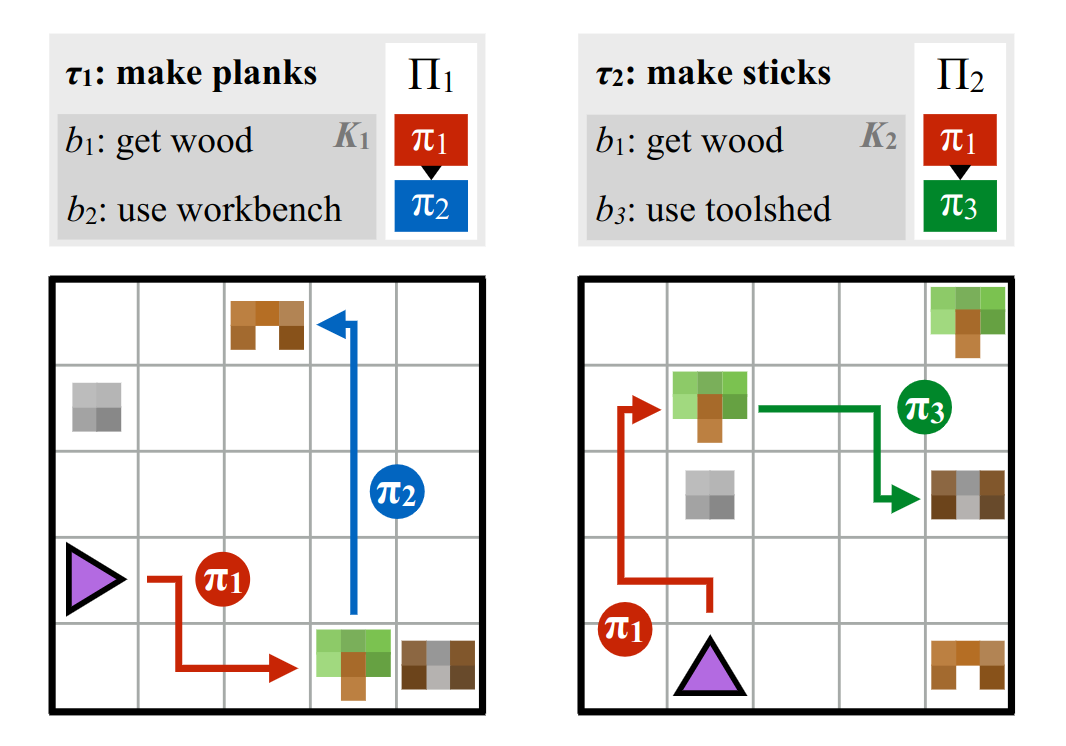

To demonstrate the approach followed in this paper, I will use the example provided in the paper shown in the figure below :

In this simple grid world scenario. we have two tasks:

- $\tau_1$ requires an agent to make plans by first collecting wood and then using the collected wood on a workbench

- $\tau_2$ requires the agent to make sticks by first collecting wood and then taking the wood to a toolshed

At the onset, we see that the first step in both of these tasks is to collect wood. Thus, if an agent learns a sub-policy to collect wood, it can reuse it for both tasks. Each subtask can be associated with a symbol $b$ and the associated policy by $\pi_b$. Now, given a set of learned symbols $b_1, b_2,\dots$ and the corresponding sub-policies $\pi_{b_1}, \pi_{b_1}, \dots$, a high-level task can be described by a sequence of symbols, which the authors call a sketch.

The sketch is akin to a word using these symbols and thus, follows the basic rules of language. Given a sketch, a complex policy $\Pi_b$ can be executed by executing a sequence of policies. To make this technically feasible, the policy executions come with termination conditions that signify the duration for which a policy needs to be executed, something that is very standard in Policy-based.

Thus, the authors recast the hierarchical problem as a problem of modular sketches using language symbols. Additionally, by being associated with symbols, the policies end up being more interpretable.

Going a bit deeper into the technicalities for the interested folks, the authors model the multi-task setting by assuming the tasks to be specified by the reward and initial distribution $(R_\tau, \rho_\tau)$. AT any time step, a subpolicy selects either a low-level action $a \in \mathcal{A}$ or a special stop action indicating termination. They use Policy gradients for the optimization with the crucial factor of having an actor per symbol but one critic per task. Since actors can participate in multiple tasks, by constraining the critic to task, they are able to baseline policies using task-associated values. Finally, to tackle the issue of sparse rewards by using a curriculum learning approach, where the learner is initially presented with shorter sketches, which are progressively increased in length as the learner learns the sub-policies.

Idea 2 - Reward specification via grounded Natural Language

Source:

While approaches like policy sketches are very powerful in composing policies together using the symbolic capabilities and inherent compositional structure of language, they still require hand-designed rewards per task. This is something that is prevalent throughout the RL literature.

The fundamental issue with this is that reward signals can be expensive to design in the real world and they usually require knowledge about the true state. On real-world tasks, however, RL agents usually have only access to pixel observations, that could be generated for latent states, for example. A common alternative to reward design is to hand-label goal images or collect demonstrations that can be used to teach an RL agent reward signals. This is a labor-intensive process as well.

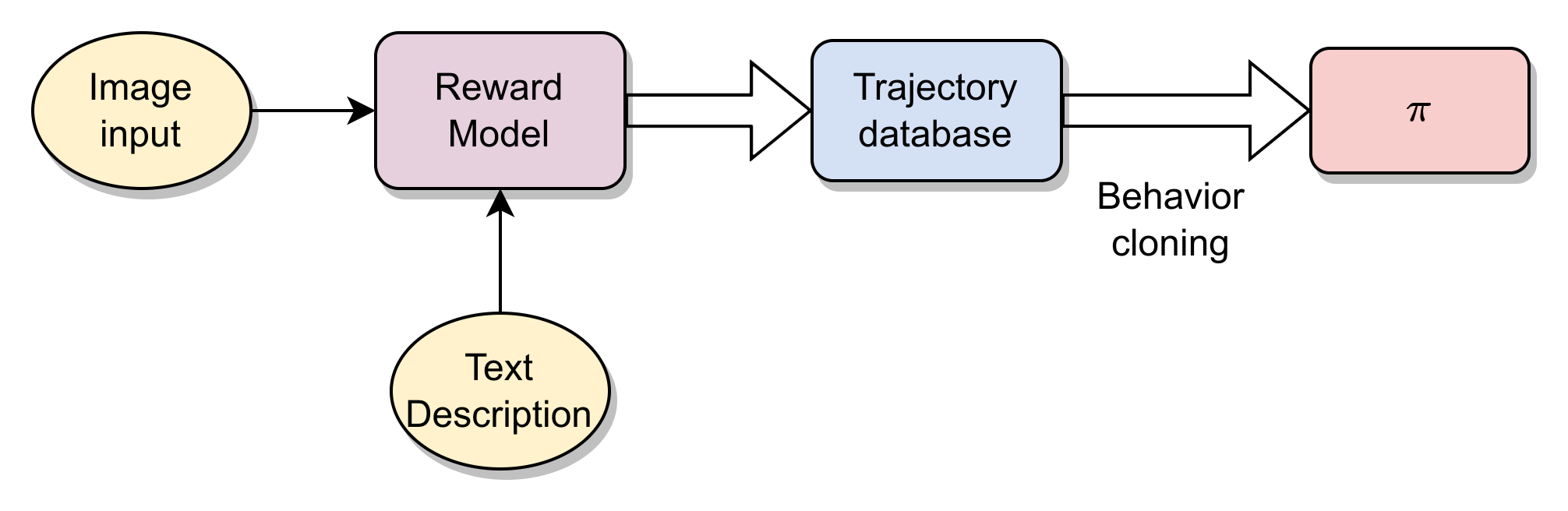

The authors of this paper take a different route by leveraging text descriptions. Specifically, language can be used to describe a task by providing the agent with descriptions of a goal and/or spatial relationships between the entities in the environment. When combined with the observation, this can be used to compute the proximity of an agent to the goal and thus, help guide the agent. The authors in this work specifically use language in the form of spatial relationships between entities. For example, a sentence like ‘A on the left of B’ would be interpreted as the x coordinate B being greater than that of A. By using multi-camera scenes, they are able to associate each description with a symbol by comparing the camera view that matches the condition.

Once the labels have been generated, they train the reward model using a contrastive loss where the model essentially predicts which caption matches which image in a sampled batch of random images. Crucially, the aim is to maximize the cosine similarity between the image and text embeddings of the correct pairs and minimize the cosine similarity of the embeddings of the incorrect pairs.

Once this has been achieved, the learned model can be used to provide rewards to RL policies. For this, they first learn several tasks using RL and the reward model. They create a large dataset of the rollouts of the learned policies and pair each trajectory with the goal text description of the tasks it was trained to learn. Finally, this data is used for supervised learning for predicting actions using text and images. The process has been visualized in the figure below:

Conclusion

In this post, we have seen two ways of using language for RL. There have been a lot of other ways recently in this direction. Some examples of these are

-

augment policy networks with the auxiliary target of generating explanations and use this to learn the relational and causal structure of the world

-

use language to model compositional task distributions and induce human-centric priors into RL agents.

Given the growth of pre-trained language models, it is only a matter of time before we see many more innovative ideas come around in this field. Language, after all, is a powerful tool to incorporate structural biases into RL pipelines. Additionally, language opens up the possibility of easier interfaces between humans and RL agents, thus, allowing more human-in-the-loop methods to be applied to RL. Finally, the symbolic nature of natural language allows better interpretability in the learned policies, while potentially making them more explainable. Thus, I see this as a very promising direction of future research